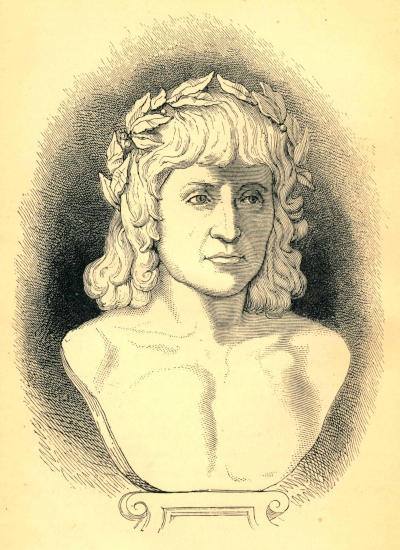

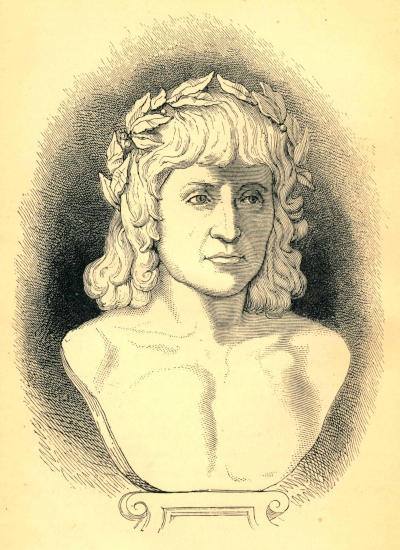

Andrea Mantegna.

From the bronze bust, attributed to Sperandio, in Sant’ Andrea, Mantua.

Title: Mantegna and Francia

Author: Julia Cartwright

Release date: July 11, 2025 [eBook #76481]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Scribner and Welford, 1881

Credits: Ginirover and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

[i]

ILLUSTRATED BIOGRAPHIES OF

THE GREAT ARTISTS.

ANDREA MANTEGNA.

FRANCESCO RAIBOLINI,

CALLED

FRANCIA.

[ii]

The following volumes, each illustrated with from 14 to 20 Engravings, are now ready, price 3s. 6d.:—

ITALIAN, &c.

TEUTONIC.

ENGLISH.

The following volumes are in preparation:—

* An Edition de luxe, containing 14 extra plates from rare engravings in the British Museum, and bound in Roxburgh style, may be had, price 10s. 6d.

Andrea Mantegna.

From the bronze bust, attributed to Sperandio, in Sant’ Andrea, Mantua.

[iii]

“The whole world without Art would be one great wilderness.”

By JULIA CARTWRIGHT

AUTHOR OF “VARALLO AND HER PAINTER,” ETC.

NEW YORK

SCRIBNER AND WELFORD

LONDON: SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON

1881

[iv]

(All rights reserved.)

[v]

Although no separate biography of Mantegna has been published in England, his life and works have been the subject of much study in other countries during recent years. The thanks of the writer are especially due to Dr. Woltmann, the author of the biography of the painter in Dr. Robert Dohme’s “Kunst und Künstler,” to M. Armand Baschet, Canonico Willelmo Braghirolli, and Dr. Karl Brun. It is to be hoped that before long the last-named of these scholars will give the result of his researches to the public in a complete work on this remarkable man, who was both one of the greatest artists and one of the most striking personalities of the Renaissance.

With regard to Francia, materials for the history of his life are far less plentiful, and are to be found almost exclusively in the works of Bolognese writers, of whom Malvasia and Calvi are the fullest and most trustworthy. In offering this little work as a guide for the use of those who have not the opportunity of studying the master’s works for themselves the author has only to add that the pictures mentioned have been carefully examined, and their descriptions written on the spot.

J. M. C.

[vi]

| PAGE | |

| MANTEGNA. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Early Years and Work at Padua. A.D. 1431-1457 | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Work at Verona and Mantua. A.D. 1457-1470 | 12 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Camera degli Sposi. A.D. 1470-1474 | 21 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Work at Mantua and Rome. Engravings, A.D. 1474-1490 | 29 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Triumphs of Julius Cæsar. Drawings, A.D. 1490-1500 | 38 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Last Works and Death—His Influence on Art. A.D. 1500-1506 | 50[vii] |

| FRANCIA. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Early Art in Bologna. A.D. 1300-1450 | 65 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Early Life and Works. A.D. 1450-1500 | 75 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Friendship and Influence of Raphael. A.D. 1500-1506 | 86 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Frescoes of St. Cecilia’s Chapel. A.D. 1506-1509 | 94 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Last Works and Death. A.D. 1509-1517 | 102 |

| The Principal Works of Mantegna | 109 |

| The Principal Works of Francia | 114 |

| Chronology | 119 |

| Bibliography | 121 |

| Index | 122 |

[viii]

| PAGE | |

| MANTEGNA. | |

| Bust Portrait of Mantegna | Frontispiece |

| Meeting of Lodovico Gonzaga and his son, the Cardinal Francesco | 26 |

| The Entombment (engraving) | 35 |

| Judith with the Head of Holofernes (drawing) | 37 |

| Part of the Triumphs of Julius Cæsar | 42 |

| The Madonna della Vittoria | 46 |

| Virgin and Child with St. John and the Magdalen | 48 |

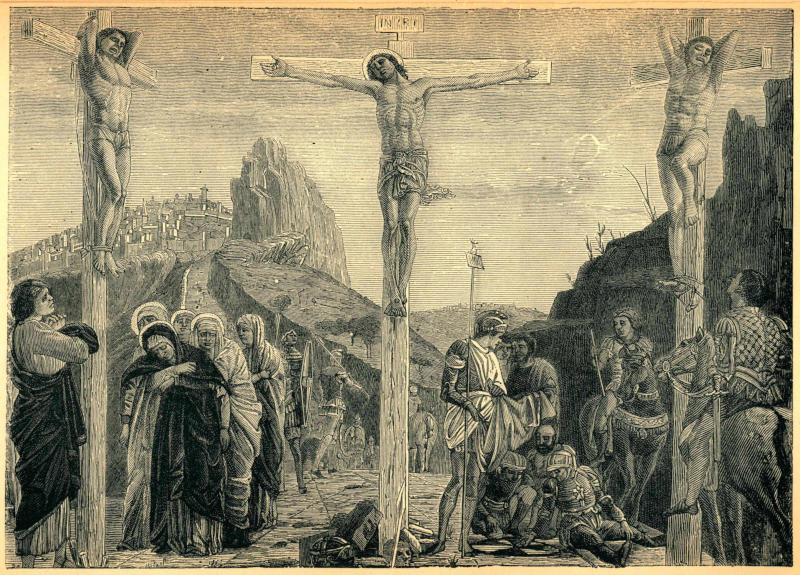

| The Crucifixion | 58 |

| FRANCIA. | |

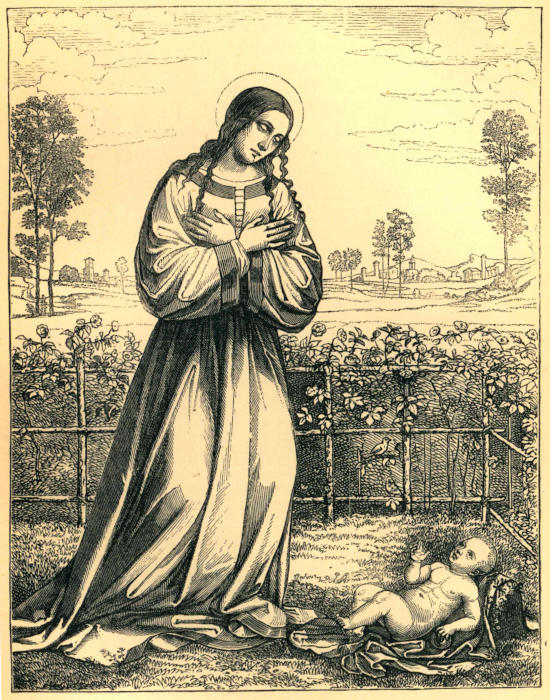

| Portrait of Francia | Frontispiece |

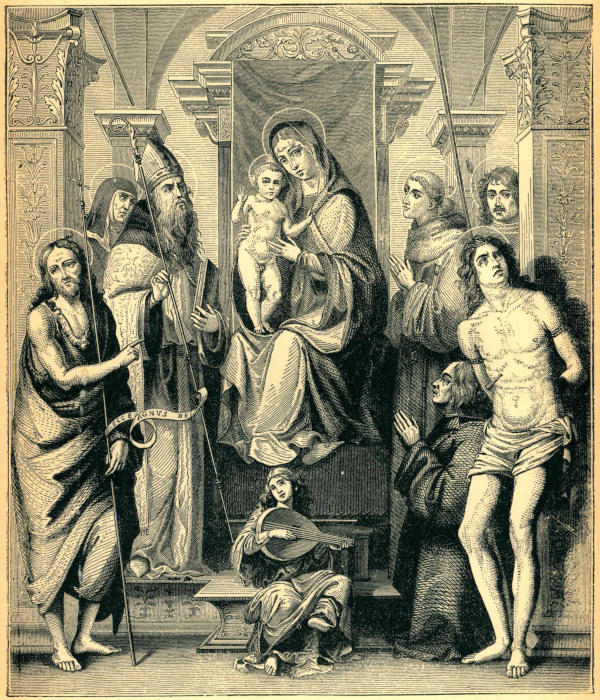

| The Virgin enthroned with Saints | 80 |

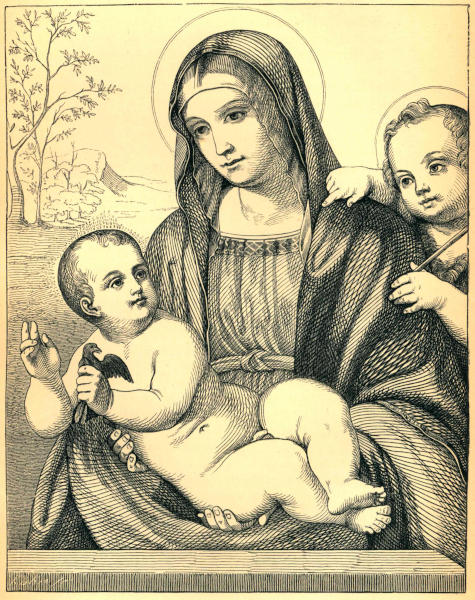

| Madonna and Child with the Bird | 85 |

| Deposition from the Cross | 89 |

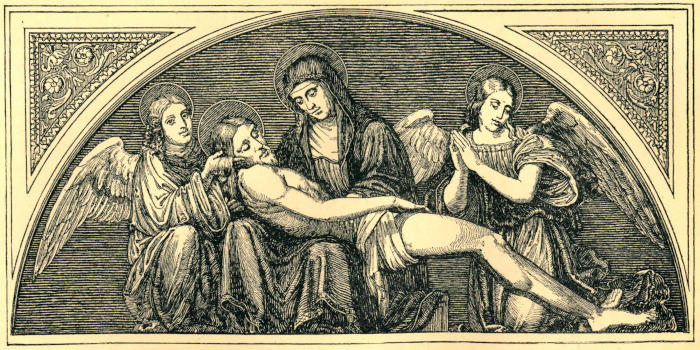

| A Pietà | 91 |

| The Madonna of the Rose-Garden | 101 |

[1]

Among the different schools of painting which flourished on the mainland of North Italy during the fifteenth century, that of Padua was the only one which attained more than a merely local importance. Independent of Byzantine traditions and strikingly peculiar in its characteristics, it rivalled for a time and even surpassed the Venetian school in the vigour and individuality of its art.

A Paduan by birth, Andrea Mantegna became the greatest master of his day, and left the stamp of his powerful genius not only on the schools of neighbouring cities, but on the whole artistic world. By his own achievements, and still more by the greatness of his aims, he stands foremost among the men of his generation who carried on the work of the Renaissance and prepared the way for the splendid age that was to follow.

This development was the more remarkable, because until the fifteenth century we do not hear of a single Paduan artist of note. Giotto had left the frescoes of the Arena Chapel within the walls of the “learned city,” and [2]Umbrian influences had later reached her students through Gentile da Fabriano, but these seeds were slow in bearing fruit. The men who painted in the famous basilica of Sant’ Antonio were mostly foreigners. Jacopo d’Avanzo and Altichieri of Verona, Giusto of Florence, belonged to other Italian cities, and although a Paduan guild existed and increased steadily in numbers the results were poor, and the few works which its members produced were feeble imitations of Giottesque or Umbrian originals.

The first to raise Paduan art out of obscurity was Francesco Squarcione, who, although “not the best of artists himself,” undoubtedly gave a new direction to painting in his native city, and in a measure earned the title of founder of the school, which has been liberally bestowed upon him. Born in 1394, and by profession a tailor and embroiderer, Squarcione early devoted himself to art, and having inherited some fortune from his father, spent his youth in travelling both in Italy and Greece.[1] During his travels he collected a considerable number of pictures, and made drawings and took casts of ancient marbles, which on his return to Padua he exhibited for the teaching of young artists. By these means he soon obtained great reputation as a master, and as many as a hundred and thirty-seven pupils, he himself tells us, were trained in his school.

A man of excellent judgment in art, but of slender powers of execution, who knew how to attract talented pupils to his studio, and who employed them in the production of works which bore his name, is the universal verdict passed upon Squarcione by early writers. The truth of this testimony is tolerably well proved by the curious difference of style visible in the only two authentic works of his that remain, an altar-piece in the gallery of Padua, and a Madonna painted for the Lazzara family. The former is a coarse and unpleasant work, with the hardness [3]of line and heavy colouring that mark Zoppo and the inferior Squarcionesques, while the latter in the dignity of its pose and careful modelling bears evident traces of Mantegna’s hand. Squarcione no doubt possessed a quick eye for discerning talent, and it is his lasting claim on the gratitude of posterity that he at once saw and appreciated the rising genius of the young Mantegna.

Andrea Mantegna, the greatest of Lombard masters, was born in the neighbourhood of Padua in the year 1431. His father, Biagio, is supposed to have been a small farmer, and Vasari tells us that in his childhood Andrea herded cattle until Squarcione, struck by the boy’s talent for drawing, adopted him as his own son.

In November, 1441, Mantegna’s name is entered on the registers of the Paduan guild as Squarcione’s foster-child, and seven years later he painted an altar-piece for the ancient church of Santa Sofia. Of this youthful work contemporaries speak with high praise as bearing marks of a practised hand, but it had already disappeared in the seventeenth century, and the earliest painting of Mantegna that now exists is the fresco above the portal of Sant’ Antonio. In this lunette, which bears the date of 1452, the two saints Anthony and Bernardino are represented supporting the sacred monogram; but the figures are too much damaged to be a fair test of the young artist’s style, and the work is chiefly interesting as a proof of the high reputation in which he was already held by his fellow-citizens.

It is to the frescoes of St. Cristoforo’s chapel in the church of the Eremitani friars that we must turn in order to form a correct idea of Mantegna’s powers during this time. Here we see him carrying the principles which he had learnt in Squarcione’s workshop to their furthest limits, and with the boldness of genius venturing on new [4]and untried paths. Here too we find him painting side by side with the best of Squarcione’s other pupils, and we have an opportunity of comparing his work with that of artists who had been formed on the same models.

This chapel, which stands to the right of the high altar, at the east end of the great Eremitani Church, belonged to the Ovetari family, whose last representative, dying in 1443, had left a sum of seven hundred gold ducats to be spent in decorating its walls with frescoes illustrating the history of St. James and St. Christopher. Squarcione received the commission from the dead man’s heir, and between the years 1448 and 1458, the walls, apse, and ceiling were covered with frescoes by his different pupils.

Thus, only a few steps from the garden which encloses Giotto’s Chapel, another great series was painted, to become for the schools of North Italy what the Brancacci Chapel had been for Florence.

Less fortunate than the celebrated frescoes of the Carmine, these paintings have suffered much from the damp of the walls, and a great part of the subjects in the apse, as well as several figures in the martyrdom and burial of St. Christopher, are completely destroyed. Other portions are still in good preservation, and afford excellent examples of the peculiarities of the Paduan school and the studies which laid the foundation of Mantegna’s subsequent greatness.

The leading feature which marks the work of all Squarcione’s scholars, and was to attain its highest artistic development in Mantegna’s later conceptions, is the sculptural treatment of form, which was a direct result of an exclusive study of ancient statues. Painting in their hands becomes more plastic than pictorial, the forms are sharply defined, the drapery falls in the small folds of ancient bas-relief, while the severity of the whole is relieved by rich decorations in the shape of festoons of fruit and foliage, which, when unskilfully managed, give a heavy and over-loaded [5]effect. This plastic tendency sprang from the discovery, then first dawning upon the men of the Renaissance, that the principles of the highest art are to be found in the antique, and was so far as it went true and laudable in its aim. But in the case of the Squarcionesques this study of classic statuary was not combined with sufficient knowledge of nature, and, therefore, frequently degenerated into a lifeless rigidity and absence of expression, if not into positive ugliness and coarseness of form.

This stiffness and want of vitality strike us at once in the four Evangelists on the ceiling of the chapel, wrongly ascribed by Vasari to Mantegna, and in the upper frescoes of St. Christopher’s life, attributed to three different artists—Marco Zoppo, Bono of Ferrara, and Ansuino of Forli. These last-named subjects are not without a considerable degree of skill in perspective and composition, but are alike marked by the same rigidity of form and metallic coldness of colouring. The feeblest of the three is Bono’s representation of St. Christopher bearing the child through the river, a work which, in awkwardness, incorrect drawing and truly painful ugliness, seems to exaggerate the worst faults of the Paduan school.

On the other hand there is a decided advance in the frescoes of Niccolo Pizzolo, the only one of the Squarcionesques who approached Mantegna’s style, and whose improved colouring and greater nobleness of type are best explained by the discovery that he had worked with the Florentines, Donatello and Filippo Lippi, during their residence in Padua. To him Vasari ascribes the figure of the Eternal between St. Peter and St. Paul on the dome of the tribune, and later critics have recognised his hand in the “Call of St. James and St. John” and “St. James exorcising Devils” on the upper part of the left wall. But the finest of all his works here is “The Assumption,” in the apse, a fresco [6]which in joyous life and freedom of movement so far surpasses the ordinary manner of the Paduans that one of the best critics, Dr. Woltmann, pronounces it to be by Mantegna’s hand. Against this we have the testimony of the anonymous traveller of the sixteenth century, who says decidedly that Andrea painted the lower part of the right and the whole of the left wall, but that “The Assumption” and cupola are by Pizzolo. Vasari is silent on this point, but remarks that Pizzolo’s works in this chapel yielded nothing in excellence to those of Andrea, and probably the best solution of the question is to accept both “The Assumption” and the upper frescoes of St. James’s life as the joint composition of the two artists, or at least to allow that they were partly designed by Mantegna.

In the midst of Pizzolo’s labours in the Eremitani Chapel his promising career was cut short by a violent end. He had, it appears, an unlucky habit of taking part in street brawls and riots, and one evening as he was returning home from his work he was attacked and slain by some unknown persons whose enmity he had excited.

Mantegna was now left alone to complete the unfinished work, and whatever uncertainty rests on his share in the earlier frescoes there is no doubt that the six remaining subjects are entirely by his hand. In each of these we see some clearer revelation of unfolding powers. Step by step some fresh difficulty is overcome, some new knowledge gained, until by slow degrees the battle is won, and the mastery over human form is complete.

In the fresco of “St. James baptizing Converts” the statuesque air of Squarcione’s school is still strongly felt in the principal figures. The action is stiff, and the faces are mostly wanting in expression. But the spectators of the ceremony are, on the contrary, full of life and animation. Nothing can be more natural than the two children who look on with wondering eyes—the taller of the two [7]holding a water-melon in his hand, while the smaller one presses close to his side—or the youth under the colonnade in the act of turning round to speak to a figure whose face is concealed by a pillar. If from these we turn to the decorative part of the fresco, the winged angels in the upper corners at once remind us of the charming groups of children on Donatello’s bronzes in Sant’ Antonio, and prove how attentively Mantegna must have studied these recently finished works of the Florentine master. The beneficial influence of the great sculptor had already appeared in the earlier frescoes of the Eremitani, and from his example Andrea now learnt how to combine the study of nature with sculptural treatment, and to adopt a more elevated type of human form.

The next subject, “St. James before Herod,” reveals a new feature, afterwards to become prominent in his career, in the accurate knowledge of Roman costumes and classical architecture which is here displayed. One of the finest figures is that of a soldier leaning on his lance in the left-hand corner of the picture, an ancient Roman, in whom we recognise immediately the painter’s own portrait, from the close resemblance which his strongly marked features and massive brow bear to the bust on Andrea’s tomb at Mantua. Both of these frescoes show considerable skill in perspective, but in the next, “St. James blessing a kneeling Disciple on his way to Execution,” Mantegna boldly ventures on an experiment that is altogether new. For no apparent reason, but purely as a trial of skill, he suddenly alters the point of sight to a low level, and while the feet of the foremost figures appear to stand on the edge of the picture the lower extremities of those in the background vanish altogether. The difficulties thus created are on the whole correctly solved. Each figure is carefully foreshortened, and the Roman arch under which the procession passes is drawn in admirable perspective, but freedom [8]of action is impaired, and the whole suffers from an unpleasant sense of effort and unnatural constraint. Perspective was in those days a favourite branch of learning in the University of Padua, and Mantegna, whose vigorous genius took pleasure in the driest studies, seems to have derived this strange passion for applying its laws to the human form from Paolo Uccelli, a Florentine who had lately visited Padua. In his ardour to accomplish his self-imposed task he failed to see the mistake of subjecting living figures to the rules of architecture, and of treating them as existing solely in order to demonstrate a scientific problem.

But at the time the young painter’s exhibition of skill excited the utmost admiration, and both Daniele Barbaro and Lomazzo praise him as the first artist who opened men’s eyes to the true principles of perspective.

If we are to believe Vasari, Squarcione, who till now had been as proud of his pupil’s growing fame as if it were his own, suddenly altered his tone and openly blamed Mantegna for the stony rigidity of his figures, declaring that they were mere copies of marble statues, altogether devoid of life and expression.

The reproach, although not wholly undeserved, was a curious one in Squarcione’s lips, but the real cause of the breach which took place between the master and scholar was Andrea’s connection with the rival workshop of Jacopo Bellini. The Venetian painter, with his two sons, Gentile and Giovanni, had lately taken up his abode at Padua, and a strong friendship had sprung up between Mantegna and the members of his family which before long led to the marriage of the young Paduan with Jacopo’s daughter Niccolosia. Their union took place while Mantegna was actually engaged on the Eremitani frescoes—probably about 1454 or 1455, since in 1458 he had already two or three children—and becomes an important fact in art history as [9]strengthening the ties between these distinguished artists. The influence each was to exercise on the other was destined to prove great and lasting. Jacopo Bellini, who had spent some time in Florence, was probably instrumental in leading Mantegna to follow Donatello and Uccelli’s models, while from Giovanni, Andrea would learn the softer colouring and delicate feeling that impart so pure a charm to those well-known Madonnas which fill the churches of Venice. Mantegna, on his part, gave back at least as much as he took, and no one can doubt that Gian Bellini owed to his brother-in-law in a great measure his knowledge of classical architecture and perspective, as well as the sculptural cast of drapery, that distinguish his pictures from those of earlier Venetian masters. In all probability this new influence, rather than Squarcione’s jealous reproaches, was the cause of the marked improvement visible in the later frescoes. The principal figures in the “Execution of St. James” are more life-like; there is less hardness in the modelling and laying on of shadows, while the background, with its winding road and rocky terraces crowned with olive-trees, is an exact copy of a Lombard hill-side. Nothing, indeed, is more striking in these frescoes than the close attention to natural objects, which shows how strongly realistic was the bent of our painter’s genius, in spite of his Squarcionesque training and love of antique statuary. He not only fills his backgrounds with faithful reproductions of Italian landscape and streets, with red roofs, arched loggias, or vine-trellised arbours, but recalls every detail and renders the furrows and wrinkles of old age, the ragged coat or torn shoe, with an accuracy that is almost painful.

The eagerness with which he sought difficulties and his courage in grappling with them meet us again in the foreshortened rider who looks on at the Saint’s martyrdom, and is still more triumphant in the bold action of the men [10]who drag away the dead body of the giant Christopher, in itself a masterpiece of perspective which served as a model for Titian and other Venetians in dealing with similar subjects in future years.

Unfortunately these two last frescoes, “The Martyrdom” and “Burial of St. Christopher,” are much injured, and some of the chief figures are completely obliterated. The portions that remain justify the praises of former critics who pronounced these to be the finest of the whole series. Here at least Squarcione’s reproach is refuted, the stony look of the faces has given place to warm flesh-tones and softer modelling, and the band of archers assembled under the vine-trellis in the scene where the saint is to meet his doom are remarkable for their energetic action and expressive faces.

According to Yasari, in this last subject, Mantegna represented Squarcione himself in the character of a fat archer, as a proof that he knew how to draw from living models, and the same writer mentions several other contemporary personages whose portraits are also introduced. Especially interesting in our eyes is the group, in the right-hand corner of “The Martyrdom,” of an elderly man standing between two younger figures, one of whom wears a red cap. The Venetian costume of these three spectators, and a certain resemblance of one of the youthful heads to a medal bearing the likeness of Gentile Bellini, go far to confirm the truth of Crowe and Cavalcaselle’s supposition that here we have portraits of Mantegna’s father and brothers-in-law, who were all in Padua at the time, and whom he would very naturally introduce among his other friends.

With these frescoes Andrea’s labours in the church of the Eremitani end, and the decoration of the chapel, with which Squarcione’s pupils had been intrusted some ten years before, was finally completed.

[11]

If from details of execution we pass to consider the work as a whole, it must be owned that the general impression left upon the spectator’s mind is one of coldness and severity. These stern and vigorous figures which look down upon us from the walls awe us by the power and reality of their presence; they impress us by the accurate science and years of assiduous labour which they reveal, but they fail to touch the heart or delight the eye; they are wanting in that sense of beauty which, is so conspicuous a feature in Mantegna’s later work. If he had painted nothing else he would have left behind him the reputation of a master of strong realistic tendency, who solved difficult problems and attained a remarkable degree of proficiency in drawing and anatomy, but lacked the qualities necessary for the highest class of art.

Fortunately for us Mantegna’s activity does not end here. The frescoes of the Eremitani were only the first stage in a great career, and as we contemplate them we can always reflect with satisfaction that these powerful works, in their grimness and austere dignity, in their curious display of scientific knowledge and minute attention to detail, were the preliminary studies, by means of which he reached the perfection of after years, and achieved the ultimate successes that were to make his name celebrated.

[12]

The exact date of the completion of the Eremitani frescoes is uncertain, but they were probably finished by 1458, perhaps earlier. Mantegna was still a young man, not more than six or seven-and-twenty, but in actual power as well as in reputation second to no living painter in North Italy.

We have already noticed the chief influences brought to bear on his early training. One by one we have watched him discover and assimilate, with the same clearness of intellect and indefatigable energy, the peculiar virtue of each successive artist with whom he was brought into contact. We have seen him add Florentine principles to Squarcione’s teaching, learn from Donatello how to combine the study of nature with the laws of sculpture, gain from Uccelli that knowledge of perspective which had for him so subtle a fascination, and last of all temper this fiery genius under the gentler spell of Gian Bellini’s more genial art.

Another and a very important element in his development was the constant intercourse which he maintained with the most learned Paduan scholars, and the keen pleasure with which he joined in their antiquarian researches in the neighbourhood. He accompanied Felice [13]Feliciano, a famous collector of inscriptions, on several excursions in the environs of Verona and the Lago di Garda for the express purpose of examining classical remains, and in 1463 this same Feliciano dedicated his work on ancient epigrams to the painter, whose learning he extols in the highest terms. One result of these explorations in the classic ground of Sermione appears in the fragments of Latin inscriptions which are repeatedly introduced, in the Eremitani frescoes, and on one Roman portico the name of Vitruvius Cerdo, a Verona architect of ancient days, is still distinctly legible.

This practice was a common one with many of the artists of Squarcione and Mantegna’s school, who, in their genuine enthusiasm for classical art, copied antique monuments and inscriptions with the minutest accuracy, and afterwards used them as accessory portions of their own compositions. We have a notable example of this habit in the drawing of a pagan altar bearing an inscription to the effect that it was found in a vault of the Baths of Caracalla, then known as the Antonine palace at Rome. The drawing, evidently by the hand of some Paduan artist, is now preserved at Christ Church, Oxford.

Besides Feliciano, Andrea numbered among his intimate friends several eminent scholars then studying at the University of Padua, such as Matteo Bossi, afterwards Abbot of Fiesole, and the Hungarian bishop Giovanni Pannonio, who celebrated the artist’s genius in Latin verse as early as 1458, and whose portrait Mantegna painted in the same year.

This rare degree of culture which made him the friend of scholars, this genuine delight in classical studies and antique art, was destined to supply our master with some of his highest inspirations, and ultimately render him the foremost representative among painters of that enthusiasm for antiquity which was the ruling passion of Italy in the fifteenth century.

[14]

During the years that Andrea was employed on the Eremitani frescoes we hear little else of his private life excepting that he married Niccolosia Bellini, and became estranged from his old master Squarcione, while two panel pictures, the Brera Altar-piece which he painted in 1454 for Santa Giustina, and the “St. Euphemia” now at Naples, are the only other works that are left us of this period. In the former, a vigorous but not very pleasing work, St. Luke is represented writing at a table between four single figures of saints, while above we have a Pietà with the Virgin, St. John, and four other saints. Far more graceful in conception is the St. Euphemia standing in her garlanded niche with the lily in her hand and the lion beside her. This admirably drawn figure in attitude and form closely resembles an antique statue, and will bear comparison, with the best of the later frescoes.

So far, Andrea’s works had been confined to Padua, but his fame had spread far beyond his native city, and before he had finished his labours in the Eremitani, pressing invitations to move to Mantua had reached him from Lodovico Gonzaga, Marquis of that principality. This prince, a generous patron of letters as well as a brave soldier and wise ruler, was anxious to make his court a centre of art and learning; and, having failed in his efforts to attract the aged Donatello, spared no pains to secure the services of the Paduan artist, whose rising genius was already eclipsing that of all others. As early as 1456 we find Lodovico entering into communication with Andrea, first by letter and then through the sculptor Luca Fancelli, a confidential agent of the Marquis. His offers were liberal; fifteen ducats a month, lodging, firewood, and sufficient wheat to feed the members of his family, who are reckoned as six in number; besides, he proposed to assist him on his journey to Mantua by sending a boat to meet him.

Mantegna lent a willing ear to these proposals, but his [15]hands were full, and flattering as were Lodovico’s entreaties and assurances of good-will, he was slow to comply with the request. In his letters he assigns first one reason, then another, for delaying his departure. First, he asks for time to execute an order given him by Gregorio Corraro, Abbot of San Zeno of Verona, and protonotary to the Apostolic See. Then he begs for six months more to complete the work, then for another respite in order to do a little piece for the Podestà of Padua. The Marquis bore all these delays with unalterable patience and courtesy, while he never for a moment relaxed his efforts to bring the artist to Mantua, and redoubled his assurance of favour. If Andrea will only come, he says again and again, and himself prove the truth of the promises made to him, he will every day of his life find greater cause to rejoice that he has entered the service of the Gonzagas. When the summer of 1459 came and the protonotary’s altar-piece was still unfinished, Lodovico suggested as a last resource that the panels should be brought to Mantua and completed there. To this proposal the abbot was too wise a man to consent, and he would not even allow Mantegna to visit Mantua for a day until the picture had been safely delivered into his hands.

This altar-piece, of which we hear so much in Lodovico’s correspondence with our master, was the “Madonna and Saints” in San Zeno, of Verona, taken to Paris in 1797, but now restored (without its predella) to its place, and one of the finest religious compositions that Andrea ever painted. All the chief characteristics of Andrea’s Paduan time are here brought together in a more elevated form, and for the first time we realise fully how great was the progress he had made since the days when he began to paint in the Eremitani Chapel. Nothing can exceed the simple dignity and grace of the youthful virgin, who sits erect under a portico decorated with a frieze of children bearing [16]festoons of fruit, through which we see a thick growth of trees, and open space of blue sky beyond. On the pillars of the portico are medallions in which Andrea has after his usual habit introduced reliefs of classical subjects, one of which is a horse-tamer, evidently copied from the famous “Twins,” of Monte Cavallo, and curious as adopted by a painter who had not yet visited Rome. The saints who stand in the groups on either side of the Madonna’s throne are still too much treated as isolated figures, but each statue-like form has a grandeur of its own, and the graceful heads of the young St. John and St. Lawrence contrast finely with those of the aged apostles and fathers of the Church, while in the boy-angels who play on the steps of the throne, or sing with wide-parted lips, we have the first of those child-faces whose laughing eyes look down from many of Mantegna’s pictures and seem to give us a foretaste of Raphael’s sweetness. Unfortunately, the different parts of the predella that belonged to this beautiful altar-piece are scattered in different galleries, the “Gethsemane” and “Ascension” are at Tours, the “Crucifixion,” in the dramatic action of its varied group by far the finest of the three, is in the Louvre.

According to Vasari, Mantegna painted several other pictures in Verona, but the only other traces of his work now remaining in that city are some equestrian figures and chiaroscuro decorations on the façade of a house near San Fermo Maggiore, and we have no proof of his ever having resided there.

The “little piece” which Andrea executed for Giacomo Marcello, Podestà of Padua, has been identified in the “Christ on the Mount of Olives” of the Baring collection, a work in which we feel the same union of plastic tendency of form and strong realism that strikes us in the frescoes. In the background, a wild and savage landscape, the desolate aspect of which is heightened by the presence of [17]cranes and birds of prey, we recognise the city of Padua with the Eremitani Church.

If we compare this picture with the well-known rendering of the same subject by Giovanni Bellini in the National Gallery, we shall see how much of the original conception and drawing the Venetian artist borrowed from his brother-in-law, and at the same time how well he knew how to modify Andrea’s severer style by his own more delicate grace and feeling for colour.

These altar-pieces were Mantegna’s last works in his native city. The patience of the Marquis was at length rewarded, and towards the close of the year 1459, Andrea moved to Mantua with his family. Soon afterwards Jacopo Bellini died, his sons moved to Venice, and the Paduan school of painting, left in the hands of inferior followers of Squarcione, came to a practical end.

But Paduan art lived on in the work of her greatest son, and the new influences and surroundings of Mantegna’s adopted city gave fresh impulse to his creative energy.

That he settled at Mantua before the end of 1459 is proved by a letter of his written to the Marquis in May, 1478, in which he speaks of having been almost nineteen years in Lodovico’s service, but it is not till the spring of 1463 that we hear of him as engaged in painting at Goïto, one of the summer villas belonging to the Gonzagas. Both this palace and the neighbouring Castle of Cavriana, where he also painted, have been destroyed, and a few panel pictures now dispersed throughout Europe are the only productions that remain of his first ten years’ residence at the Court of Mantua.

Chief among these is the Uffizi triptych, which originally belonged to a chapel of the Gonzagas, and may be the very picture to which Andrea alludes in a letter of 1464 as destined for the little chapel, and which Vasari tells us contained many small but most beautiful figures.

[18]

The “Adoration of the Magi” forms the subject of the central panel, while the “Ascension” and the “Presentation in the Temple” are represented on the wings. All three are marked by the miniature-like finish which reveals the thoroughly practised hand and loving zeal of one who took delight in carrying his work to the highest possible perfection.

In the seated Virgin, of the strong type of womanhood which Andrea seems to prefer, with the flight of cherubs encircling her head, and the patches of rough herbage starting out of the rocks behind her, we recognise the original of his own unfinished engraving, the “Virgin of the Grotto.” The red cherub-heads, which remind us of the similar wreath with which Giovanni Bellini surrounds one of his Madonnas in the Academy of Venice, are again introduced in “The Ascension.” Here the group of apostles, who gaze upwards, have more of the slender form used by Pizzolo in the Eremitani frescoes, and the panel is inferior as a whole to “The Presentation.”

This is in Mantegna’s best manner, the principal figures full of grace and dignity, the heads excellent in expression, especially that of the child sucking his finger as he leans against his mother, while Andrea’s historic feeling appears in the typical reliefs of “Moses breaking the Tables” and “Abraham sacrificing Isaac,” which adorn the altar. Another fine rendering of this subject by Mantegna is now in the Berlin Gallery, which also possesses two other works belonging to this period, a half-length “Madonna holding the Child on a Parapet,” and a portrait of an old ecclesiastic.

Probably this Madonna was the very one of which Vasari speaks as painted by Mantegna, for his old friend, the famous orator, Matteo Bossi, Abbot of Fiesole, since the frame decorated with angels and instruments of the Passion exactly corresponds with his description, and the [19]strikingly-truthful portrait may well be that of the Abbot himself, whose friendship for the painter neither time nor distance seems to have impaired.

A “Death of the Virgin,” with a view of Mantua and its lake seen through a colonnade, now at Madrid, and chiaroscuro figures known as “Summer” and “Autumn,” now at Hamilton Palace, may be mentioned as painted about 1470, when Andrea was engaged in works at the Castle of Mantua.

More interesting in the eyes of most of us are the two small pictures of the Saints Sebastian and George, two youthful figures intended to show the contrast of suffering and repose. In the “St. Sebastian” now at Vienna, Mantegna has deliberately set himself the task of representing the human form wrung by physical agony, and the divine strength of a will that can conquer pain by the power of its endurance. His success was complete, and among the countless representations of martyrdom that exist, there is scarcely a finer example than this St. Sebastian bound to the ruined column and pierced with arrows, lifting his eyes heavenwards in his mortal agony. At his feet lie broken statues and marbles, shattered fragments of the old world that was crumbling to ruins around, and which by the delicate grace of their shapes and mouldings help to associate ideas of beauty with this scene of suffering and death.

The opposite of this picture meets us in the armed “St. George” of the Venice Academy, who stands under an archway garlanded with flowers, leaning on his lance in satisfied repose of victory, with the dragon dead at his feet. His classical head is not unlike the youthful saints of the Verona altar-piece, while the highly finished character of the execution approaches the style of the Uffizi triptych, evidently painted about the same time.

To these we may add the wonderful “Dead Christ” of the Brera, a work almost terrible in its realism, and exaggerated [20]foreshortening, but which reveals in a surprising degree Mantegna’s mastery both in drawing and management of light and shade. This Cristo in Scurto was one of those daring trials of skill which he loved to attempt, not to please the eye or gratify the taste of his employers, but simply in order to overcome some difficulty or solve some problem from which a less powerful mind would have shrunk.

The satisfaction which he felt in the success of this experiment is proved by his unwillingness to part with this work, which never left his studio until his death, when it is mentioned by his son in the list of paintings that were sold to pay his debts.

In the same style as this “Pietà,” but with more attempt at decorative effect, is the picture exhibited by Sir William Abdy, in the last winter exhibition at Burlington House (1880-81). Here the dead Christ lies on a carved throne of coloured marbles, the back of which is formed by the broken tables of the law. On either side are two grandly defined forms of Isaiah and Jerome, as representatives of the old and new dispensations, between whom Christ stands. The background is more elaborate than usual. On one side is a wild tract of mountainous country, on the other a river and fertile valley, along the slopes of which we see rows of smiling villages, church-towers, and fields enclosed with hedges. In the foreground skulls and bones are scattered at the feet of the prophets, and beasts and birds of gay plumage enliven the scene. A stag and panther and a red parrot are prominent figures, but all these minor details are subdued to the leading idea in the painter’s mind. Doubts have been entertained as to the authorship of the picture, but both its general style and colouring and the presence of that weird grandeur of imagination peculiar to Mantegna are strong proofs of its genuineness.

[21]

Recent research has brought to light a series of valuable letters between the Gonzagas and Mantegna, which tell us little indeed about his existing works, but much that is of the deepest interest concerning his private life, and especially his relations with Lodovico and his family.

The Marquis had kept his word and proved himself a true friend and generous patron to the Paduan artist. Carissmé noster, dilecte noster, are the terms in which he always addresses him, and the thoughtful consideration and patience with which he treated Andrea in what must frequently have been very trying circumstances, are beyond all praise.

The first letter of the series is a complaint which the painter, writing from Goïto, addresses to Lodovico, saying that his stipend is irregularly paid, a wrong which the Marquis promptly redressed. Three years later we find him in the same liberal spirit advancing one hundred ducats which Mantegna begged in order to decorate and improve his house in Mantua.

There our painter spent the winter with his wife and three children—tutto la mia brigatela he calls them in a letter to the Marquis—and each year, when the summer [22]heats returned, he moved to a country-house at Buscoldo, where he afterwards received a grant of land from his patron.

In 1466 he paid a visit to Florence, where he had at least one friend in the learned Abbot of Fiesole, and a letter from Giovanni Aldobrandini, an agent of Lodovico, describes the great respect with which he was received, and the admiration excited by his varied accomplishments. “Not only in painting but in other ways he showed remarkable knowledge and most excellent understanding” is Aldobrandini’s testimony, and we learn from other sources that he took much pleasure in poetry, and even wrote verses himself. A sonnet of his composition addressed to a lady whose name is unknown, and written in the fashionable Platonic style of the day, has been discovered in the Mantuan archives and is given by Moschini. As a collector of antiquities he had acquired considerable reputation, and in 1472 we find the young Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga, then at Bologna, begging his father that Mantegna may be sent to him that he may have the pleasure of showing him his cameos, bronzes, and other antiques.

Unfortunately the culture and refined taste which made Mantegna so agreeable a companion were accompanied by an irritable temper, and a readiness to take offence, which rendered him the reverse of a pleasant neighbour. The most trifling contradictions were sufficient to excite furious outbursts of anger on his part, and his letters to Lodovico are full of the pettiest grievances. The Marquis, it must be said, treated him with the utmost forbearance, and spared no pains to inquire into the grounds of his complaints, however small. On one occasion he implores Lodovico to punish a tailor who has spoilt a piece of his cloth, on another he has quarrelled with a gardener and his wife who live in the same street, and complains that neither he nor his wife can leave the house without being attacked by insulting words. More serious was the lawsuit [23]in which he found himself involved with the engraver, Zoan Andrea, whom he suspected of purloining his plates, and to whom he administered a sound thrashing. Upon this Zoan Andrea had recourse to legal measures, in which Mantegna seems to have fared badly, since he was again compelled to seek the help of his powerful patron.

But of all Andrea’s quarrels, that which excited his greatest wrath was his breach with his Buscoldo neighbour, Francesco Aliprandi, whom he publicly accused of stealing five hundred quinces from a tree which grew in his garden. There is a singular combination of the pathetic and ludicrous in Mantegna’s description of the beauty of his fruit tree, with its branches so heavily laden that they touched the ground. Each day he looked upon it with fresh delight, until one September morning he found all the quinces gone, and the tree stripped and bare. His anger knew no bounds, and he did not hesitate to charge his nearest neighbours, the Aliprandi, who he was convinced bore him secret ill-will with the theft. Upon this Francesco Aliprandi, who seems to have been a citizen of good birth, denied the charge indignantly, saying that during the two hundred years his family had lived in Mantua, they had never been insulted by so vile an epithet as that of thief, and complaining of Mantegna’s disagreeable character as the real cause of all this disturbance. “No one,” Aliprandi continues, “can live near him in peace, and at the present moment he is engaged in lawsuits with no less than five of his neighbours.” Even the Marquis was forced to admit this time that Andrea was in the wrong, and, after carefully investigating the case, arrived at the conclusion that the quinces had been stolen by some unknown thief.

This ruggedness of disposition and exaggerated susceptibility which, by attaching excessive importance to the trifling cares of daily life, proved a constant torment [24]to Mantegna and those around him, remind us curiously of Michelangelo, whom in more ways than one our master resembled.

Like the great Florentine in this also, he never stooped to flattery or servile expressions in addressing his patron. On the contrary, there is from the first an independent spirit and proud consciousness of his own merit which never deserts him, and he tells the Marquis repeatedly that his coming to Mantua was a great favour on his part, and that no other prince in Italy has so industrious an artist in his service.

The boast may not have sounded well in Mantegna’s lips, but it was a true one. His activity was indefatigable, and whether he painted in chapels and palaces, or made studies for tapestry or designs from the turkey-cocks and hens which strutted in the court poultry-yard, his time and powers were unreservedly placed at Lodovico’s disposal. What we have to regret is that so little of all his splendid work is left, although when we consider the subsequent history of Mantua, it is rather to be wondered that anything has been saved from the general wreck.

In 1630, little more than a hundred years after Mantegna’s time, the city was besieged during three months by the Imperialists, and ultimately taken and sacked for three whole days. In 1797 it was again twice besieged and bombarded by the French and Austrians, and during the wars of the present century the ducal palace has been alternately occupied by French and German soldiers. This once sumptuous pile is now the dreariest and most desolate of palaces. The little life that still lingers in the old town clusters round the market-place on the Piazza delle Erbe, and grass grows on the deserted square which was once the centre of “Mantova la Gloriosa.”

Meeting of Lodovico Gonzaga and his Son, the Cardinal Francesco. By Mantegna.

In the Camera degli Sposi, at Mantua.

We pass through endless suites of spacious halls paved with marble and adorned with decaying frescoes and other [25]remnants of faded splendour, till we reach the older part of the palace known in the days of the Gonzagas as the Castello di Corte. From its windows we look down on the sleepy waters of the vast lagoon, which seems to divide Mantua from the outer world, and over miles of swampy marshes, through which “smooth-sliding Mincius” winds its way.

Here the Gonzagas hold their splendid court, here the banqueting-halls where they feasted, the ball-rooms—the scenes of their revels and masquerades—the suite of tiny apartments expressly built for the use of the dwarfs, the courtyards where the dogs were kept, are still shown. Here Mantegna painted, and here the walls of a room, now used to contain the archives, were entirely covered with frescoes by himself.

This was the famous Camera degli Sposi, on which Andrea was engaged between 1470 and 1474, and where he represented Lodovico Gonzaga and his wife, Barbara of Brandenburg, surrounded by the different members of their family.

All the frescoes have been much damaged, and those on two of the walls completely obliterated; but the groups which remain and the decorations of the ceiling are of the highest interest, and, if we except the Hampton Court Triumphs, form the most important series that we have from Mantegna’s hand.

On the east wall above the mantel-piece is the central group. Lodovico and his wife, clad in rich brocaded robes, are seated in a garden surrounded by their children, and dwarfs in the act of receiving a messenger, who hands the Marquis a letter. Neither Lodovico nor any of his family seem to have been remarkable for personal beauty, and Mantegna has not made any attempt to embellish them. He paints them exactly as they were, in the stiff costumes of the day. Barbara wears the same veiled horn-shaped [26]head-dress as in Andrea’s portrait-engraving in the British Museum; the children and courtiers are in short jackets and tight-fitting caps. Nothing is omitted that could complete the picture, which is like a page torn out of the court life of those times; a favourite greyhound lies asleep under Lodovico’s chair, and several dwarfs positively repulsive in their ugliness are introduced. They formed, we know, an important part of the household, since the Marquis kept a particular race, bred at Mantua, and reserved a whole wing of his palace, with staircases, halls, and bedrooms adapted to their stature, for their exclusive use.

Beyond the fine figure of the courtier on the right, evidently the painter’s own portrait, we have another compartment where the Marquis stands at the head of the stairs welcoming his guests, or, as Selvatico suggests, opening his arms to his son Federico, who had been in disgrace for refusing to consent to a marriage which Lodovico had arranged for him. This subject is much damaged, but on the entrance-wall is another group, the best preserved of the three, in which the Marquis meets his younger son, the boy-cardinal Francesco, on his return from Rome. The composition is stiff and the dresses awkward, but nothing can surpass the life-like character of the heads, whether we fix our eyes on the baby-faces and demure air of the children who advance to welcome their brother, or on the vigorous profiles of Lodovico and his courtiers. A tame lion crouches at the feet of the Marquis, and a view of hills and classical temples, intended to represent Rome, fills in the background. On the opposite side of the doorway the servants and pages in attendance are introduced holding their master’s horse, and several dogs in leash, all admirably drawn; while above the door itself a charming group of seven winged boys, in every possible attitude, support a tablet with the following inscription:—

[27]

The grace and freshness of these boy-angels form a striking contrast to the stiff figures on the walls, and both here and in the decorations of the ceiling our painter, released from the obligations of portraiture, allowed his fancy free play. Medallions of the Cæsars wreathed in laurel, grisaille scenes from the myths of Hercules and Antæus, Orpheus, Apollo, and the Tritons, occupy the vaulting of the ceiling; while in the centre a circular opening is painted to represent a blue sky, across which white clouds are floating by, as we see in actual reality in the Pantheon of Rome. Round this open space runs a balustrade, upon which a peacock is perched and a basket of fruit rests. Two women, a girl with a jewelled head-dress and a negress, look down from above with laughing faces, while a band of winged boys play on the edge of the stone-work.

These are the famous figures, che scortano di sotto in sù, which Vasari says excited general admiration when Mantegna first painted them in the Castle of Mantua.

Instead of treating the ceiling in the usual fashion, as another flat surface on a level with the spectator’s eye, he endeavoured to represent the figures he painted there as seen from below, and in reality looking down over the balustrade. The optical illusion is effected in a masterly way, and the playful boys, who push their heads through [28]the open stone-work of the parapet or balance themselves on its edge, are admirably foreshortened.

Curiously enough, this new principle of ceiling decoration, which in Corregio’s days was to become universal, and which Mantegna here attempted for the first time, was employed at almost the same moment by another painter, Melozzo da Forli, in his fresco of the “Glory of Heaven” in the tribune of the Church of the SS. Apostoli at Rome. Whether the two masters had ever been brought into personal contact we do not learn, but we know that Giovanni Santi, the father of Raphael, in his rhyming chronicle, gives Mantegna’s perspective the highest praise, and we may infer from this that the great Lombard’s influence had penetrated far enough south to reach the Umbrian artists.

The frescoes of the Camera degli Sposi were finished in 1474, and ten years later it is recorded that Mantegna painted in another part of the palace, known as the Scalcheria; but a ruined ceiling, with the same circular opening and sportive Loves, is all that is left of his work there.

Traces of his hand are also visible in another hall in some of the groups of a large, much-injured fresco, where the first Gonzaga is represented taking the oath as Capitano del popolo, and more especially in the children holding a tablet which once bore a now-effaced inscription.

All else has perished. The lapse of time and the more cruel ravages of man have swept away whatever other paintings once adorned these walls, and the precious fragments of the Camera degli Sposi are absolutely the only works of Mantegna that are still to be seen in this his adopted city, where he spent well-nigh fifty years of his life.

[29]

The painting of the Camera degli Sposi gave the Marquis an opportunity for the bestowal of new favours on his chosen artist, “suus Andreas,” as Mantegna proudly terms himself on the tablet where he has recorded the completion of the work. Lodovico now granted him a piece of land near the Church of St. Sebastian, in Mantua, where Andrea built a house with the help of the architect Giovanni di Padova, and decorated it with frescoes which were the admiration of his contemporaries, but which perished in the sack of Mantua.

Unfortunately his love of splendid undertakings led him into extravagance; he had already incurred heavy debts by purchasing a property at Buscoldo, and the expenses of his new house involved him in further difficulties. According to his usual habit he had recourse to the Marquis, and addressed him on the 13th of May, 1478, in a querulous letter, complaining that he is growing old, and has several sons and one daughter of a marriageable age, and yet that while others think he is basking in the sunshine of his Excellency’s favour he is in reality poorer than when he first came to Mantua. He ended by asking him to pay the eight hundred ducats required to satisfy his Buscoldo creditors, and to give him six hundred more in order to defray the cost of his new house.

Lodovico was at that time in great difficulties himself, [30]for he had been defeated by his enemies, and even compelled to pawn his jewels. None the less his reply was frank and generous. He fully recognised his obligations, and assured him that all his last pledges should be redeemed, but reminded him that of late fortune had been unfavourable to his arms, and that it was impossible for him to give what he did not possess. This letter, written in the same kindly spirit which we have often before had occasion to notice, was the last which Andrea ever received from his noble patron. Before another month had elapsed the good Marquis was dead, and had been succeeded by his son Federico.

The young Gonzaga had known Mantegna from his boyhood, and proved as kind and liberal a friend as his father to the wayward artist. He not only paid his debts, but exempted the estates which he possessed both at Goïto and at Mantua from the land-tax. All his dealings with Andrea are marked by the same generous feeling. His letters express much concern on hearing of an attack of illness which had interrupted the painter’s work; and on another occasion, when one of Andrea’s sons was ill, he sent his own doctor from Venice to attend him.

During the six years of this prince’s brief reign Mantegna was chiefly employed in painting halls at the villas of Marmirolo and Gonzaga, which have long since shared the common ruin of the summer palaces round Mantua.

His fame was now at its height. “The virtue of Andrea,” wrote the Marquis Federico, “is known to the whole world;” and in 1483 Lorenzo de’ Medici stopped at Mantua to visit our painter’s house and renowned collection of antiquities. Other sovereigns sent him pressing invitations, and all were desirous of having a work by Mantegna’s hand; but the great man was capricious, and refused most of these solicitations. Federico himself had to make his painter’s excuses in an elaborate epistle to the Duchess of Milan, [31]whose portrait Andrea flatly refused to undertake. There was no help for it, and the disappointed lady had to rest satisfied with Federico’s explanation, that since these excellent masters were so full of fancies we must be content with what they choose to give us.

But when Federico’s early death in 1484 left the rule of his principality to a mere child, Andrea, filled with anxiety for the future, and still heavily burdened with debt, began to look around him for another patron. His thoughts naturally turned to the illustrious patron of the fine arts who had recently visited his studio, and he appealed to Lorenzo de’ Medici in a pathetic letter, bewailing the losses he had sustained in the successive deaths of two generous masters, and begging to be employed, if perchance he should have any talent likely to please so magnificent a prince. What answer Lorenzo returned to this entreaty we do not learn, but he probably gave him a commission before long, since we know that it was for him Andrea painted the beautiful little Virgin of the Uffizi, which, with the master’s habitual slowness, he did not finish until the close of his visit to Rome. This little gem remains a precious memorial of the intercourse between two of the most interesting personalities of the Renaissance, and few of Andrea’s conceptions are sweeter than the blue-draped Mother gazing with drooping eyelids on the Child whom she rocks to sleep in her arms, while the peasants are seen at work in the field beyond and a band of herdsmen drive their flocks up the steep hill-side path.

After all, however, the state of affairs at Mantua was more hopeful than Andrea had imagined in his first grief for the loss of Federico; and before long the contemplated marriage of the boy Marquis Francesco with Isabella of Este renewed his connection with the house of Ferrara, whose members had been among his earliest patrons. He now painted a Madonna for the Duchess Eleanor, which Francesco [32]himself took to Ferrara, where his mother-in-law was impatiently awaiting its arrival. Most critics agree in identifying this picture with the noble Virgin, formerly in the possession of Sir C. Eastlake and now in the Dresden Gallery, a work in which the thoughtfulness of the child and tender maternal feeling of Mary are peculiarly impressive.

Very soon afterwards, in the year 1485, Mantegna began the greatest work of his whole life, the “Triumphs of Julius Cæsar,” now at Hampton Court. They were originally destined for the palace of St. Sebastian, at Mantua, which the young Marquis was then building; and a letter of the 25th of August, 1485, describes how Prince Ercole of Ferrara saw Mantegna employed on them in his studio. While engaged on this engrossing work he was interrupted in the summer of 1488 by an invitation from Pope Innocent VIII., who begged Francesco that the great Lombard artist might be allowed to decorate his newly erected chapel in the Vatican. Political reasons induced the Marquis to consent; he knighted Andrea and sent him to Rome with the most flattering recommendations.

During two years Mantegna painted in the chapel of the Vatican, and it is a subject of the deepest regret that a series of frescoes executed in his best period should have been ruthlessly destroyed by Pius VI. when he enlarged the Vatican Museum. On the entrance wall the Madonna sat enthroned, above the altar was the “Baptism,” on the side walls the “Birth of Christ” and the “Adoration of the Magi;” while Old Testament subjects and the Virtues were represented in grisaille on the ceiling, all painted, says Vasari, with the same miniature-like finish.

But Andrea did not find the Pope a liberal patron or Rome a pleasant residence. He complains bitterly in his letters to Francesco of the irregular payment which he receives, and the difference which he finds between the habits of the Vatican and those of the Courts.

[33]

Whether he was not treated with the deference to which he was accustomed, or whether failing health oppressed his spirits, his tone becomes more and more melancholy. A longing for home had seized him, and he implores the Marquis to send him a few lines of comfort, since he is now, as he always has been, the child of the House of Gonzaga, and will serve no other prince. Anxiety for his unfinished “Triumphs” is added to the solicitude which he feels for his absent family, and he entreats Francesco in the same breath to find his son Lodovico employment, and to take care that his “Triumphs” are not injured by rain coming in at the windows, since he considers them the best and most perfect of all his works.

Francesco replied in the most friendly manner, promising to attend to his requests, and begging Andrea to be careful of his health, and to return as speedily as possible to complete the “Triumphs,” which he counts the greatest glory of Mantua and his own house. But the frescoes of the Belvedere Chapel were no small task, and Andrea had, as he complains, no assistant to help him in his labours. He found means, however, to express his dissatisfaction to the Pope one day by adding another Virtue to the figures which he had designed. The Pope, who frequently visited him when at work, asked him who the last Virtue might be. “That is Discretion,” said the painter; upon which the Pope, not to be outdone, returned promptly, “Put her in good company then, and add Patience.” Another version of the story, given by Ridolf, is that he added the figure of Ingratitude as an eighth to the seven deadly sins, saying that this was the blackest of all crimes. In the following June he writes more cheerfully, describing a singular visitor he has had in the person of Zizim, brother of the Sultan Bajazet, then a captive in the Vatican, and sending his portrait for Francesco’s amusement. Another six months passed, and the Marquis wrote again, this time in [34]a very urgent strain, both to the Pope and Mantegna, saying that his marriage with Isabella of Este was to take place in January, and that Andrea’s presence was indispensable. The courier who brought the letter found the painter ill in bed and unable to move; so the wedding festivities had to be celebrated without him, and his return was delayed until the following summer, when the Pope at length dismissed him with a complimentary letter of thanks to the Marquis. Besides the small “Virgin” of the Uffizi, only one other work of Andrea’s Roman time is known to exist, a “Man of Sorrows, supported by Angels,” now in the Museum of Copenhagen, and, like the Brera Pietà, remarkable for the skill and knowledge displayed both in the drawing and distribution of light and shade.

It has often been said that during his visit to Rome, Mantegna first learnt the new art of engraving, in the practice of which he spent so large a portion of his time and powers. But if we consider, on the one hand, the variety both in style and subject of his plates, and on the other the great undertakings on which he was engaged during his last years, we shall see that this is impossible.

It is true that no fixed date in his earlier career can be assigned with certainty, but an attentive study of his engravings will, we think, result in the conclusion that his first efforts in this new branch of art belong to his Paduan days, and that he pursued it at intervals all through his career, but with increased activity during the latter part of his life. Two plates especially, the unfinished “Scourging” and the “Descent of Christ into Limbo,” bear a strong resemblance to the Eremitani frescoes, while others remind us in a similar manner of the San Zeno altar-piece and the earlier Mantuan paintings. At first his method was imperfect, but we trace a gradual improvement in the plates, in proportion as he acquired greater technical knowledge [35]in the new art and became acquainted with Maso di Finiguerra, and it may be with Schongauer’s engravings. All are marked by the same firmness of outline, by the same closely-marked shading drawn in slanting lines from right to left, and, above all, by the constant endeavour to give the print something of the charm of chiaroscuro and colour. Since, however, a whole school of engravers formed themselves on Mantegna’s style, and Zoan Andrea, Mocetto, Campagnola and others, all adopted his method and confined themselves almost exclusively to the reproduction of his works—the task of distinguishing Mantegna’s original plates is by no means easy. Of late years they have been subjected to a severe criticism, and many formerly attributed to him are now rejected. But, whether we accept twenty-four or twenty with M. Duplessis and Bartsch, or limit the number to thirteen with M. Wallis, we shall equally acknowledge how wonderfully every aspect of his genius is represented in these engravings, and how inexhaustible was that wealth of thought and imagery which, unable to find its full expression in painting, sought another channel in the sister art.

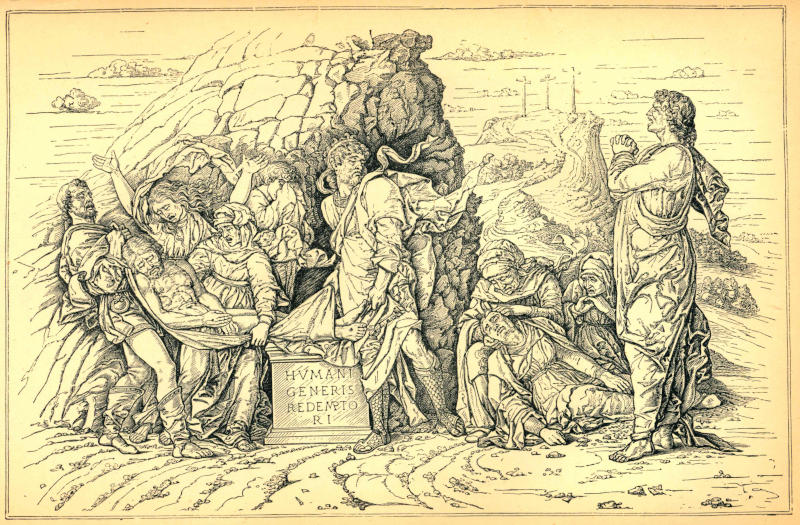

The Entombment.

From the engraving by Mantegna.

Small as is the cycle of genuine prints, they embrace a wide range of subject; pagan myths, Roman and Christian themes, are all treated in turn with the same seriousness of purpose and marvellous variety of invention. Sometimes he reproduces his own pictures—the “Virgin of the Grotto” from the Uffizi triptych, in later years we have the “Triumphs” and the “Dancing Muses of the Parnassus.” The Bacchanalia, and still more the “Battle of the Sea-gods,” remain to show us how deeply the spirit of classic bas-relief had sunk into his soul. Certain subjects there are in which he takes especial delight, which he treats with as great freshness and originality as if he had never before approached them. Such are the “Hercules and Antæus,” already represented in grisaille on the ceiling of the [36]Camera degli Sposi, and the “St. Sebastian,” which hardly yields in beauty to the sublime painting of the Belvedere. At other times he reveals some altogether new conception, as in the noble “Descent from the Cross,” which supplied the motives whence Albrecht Dürer, Luca Signorelli, Daniele da Volterra, and Rubens in turn took their inspirations. In dramatic power and intensity of feeling this plate is only equalled by the well-known “Entombment,” where all the horrors of death, all the depths of the wildest despair, seem gathered up and concentrated in that one figure of St. John wringing his hands aloft and uttering the great and bitter cry which cannot be restrained. The same strong feeling shows itself under another form in the seated Madonna, whose whole figure is swayed with the foreboding of coming anguish that mingles with her love, as she bends forward to press the Child closer to her face. But although these figures, animated with rage and despair, with a great hatred or a still greater love, are the subjects on which Andrea seemed to dwell with preference in his engravings, he returns at times to the serene repose of ancient statuary, and designs for us a group of perfect majesty in the three grand figures of “St. Andrew, St. Longinus, and the Risen Christ,” who stands between them, calm and strong, with the awe of that death which he had conquered still upon his brow.

Again, in vivid contrast with reeling satyrs and angry Tritons battling on the rough sea-waves, we have the quiet portrait heads of Lodovico Gonzaga and his wife, Barbara,[2] whose homely faces and earnest eyes look out of the same quaint costumes as on their palace walls at Mantua, and on whose brocaded robes infinite pains have been bestowed.

This is not the place to enter into further details, or a [37]whole volume might with profit be devoted to the consideration of Mantegna’s engravings, but enough has been said to show how important a part of his works they form, and how extraordinary was the genius of the man who could, in his leisure moments during the brief intervals which elapsed between his greater tasks, give to the world so rich a treasure of profound and varied thought.

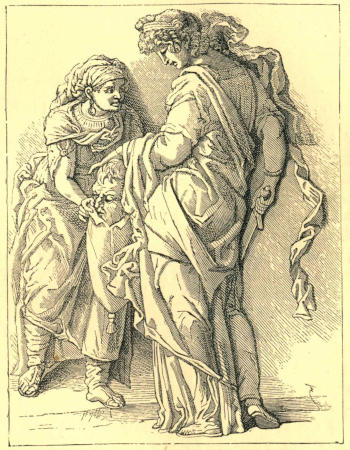

JUDITH WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES.

From the drawing by Mantegna in the Uffizi.

[38]

Mantegna, as we have already mentioned, returned to Mantua in the summer of 1490, and during the rest of that year and the whole of the following one he devoted himself without interruption to his “Triumphs,” which he finally completed in February, 1492.

This famous series consists of nine pieces of fine twilled linen, upon which Andrea painted in tempera the triumphal procession of Julius Cæsar on his way to the Capitol, after the Conquest of Gaul. The whole formed a frieze eighty feet long, and the separate compartments, each nine feet high, were originally divided by pilasters adorned with warlike ornaments.

In the first piece, the trumpeters marching at the head of the procession open the pageant with a burst of warlike music, closely followed by standard-bearers carrying pictures of Cæsar’s victories, smoking censers, and a large bust of Roma Victrix. In the second, the gods of the captive cities are borne in chariots, a colossal Jupiter and Juno foremost, then a fine Cybele, and after these come trophies of armour, battering-rams, and other warlike implements, lifted high on men’s shoulders. The costlier part of the spoil follows in the third and fourth compartments, where strong men bend under the weight of vases [39]filled with gold and treasures, and white heifers garlanded with flowers ready for sacrifice, are led by veiled priests and beautiful fair-haired youths in their white tunics and red girdles. In the fifth picture another band of trumpeters heralds the next division, and four large elephants, hung with gold chains and draperies, bear on their backs baskets of flowers and young children, who fan the flames of lighted candelabra. More trophies follow in the sixth compartment; the armour of captive princes is borne aloft on poles, and so great is its weight that one old soldier, exhausted by the load he bears, sits down to recover breath. In the next picture we reach the most interesting part of the procession—a train of captives who advance with slow and sorrowful steps, but not without an air of noble fortitude on their faces as they meet the jeers of the populace. Men and women of all ages are among them, proud chiefs, matrons of royal blood, sweet-faced maidens, a young bride with the myrtle wreath on her fair brow and a coral necklace round her throat. Close to her we see a mother bearing her youngest born in her arms and leading a boy by the hand, who cries to be taken up, while the old grandmother bends down to soothe him with caresses.

In the eighth picture, immediately following this touching group, come the jesters and hideous buffoons, who mock the prisoners with their laughter and ape-like grimaces, and a troop of musicians singing and dancing to the sound of timbrels. After these we have another company of signiferi, this time bearing the eagles of the victorious legions and the she-wolf of Rome. Their faces are turned backwards, and their eager, expectant gaze prepare us for the coming of the conqueror, who appears in the last picture seated on a richly sculptured biga with sceptre and palm in his hand, and a laurel crown, which a winged Victory is in the act of placing on his brow. At [40]his feet children shout for joy, and wave laurel boughs in his path; the multitude press round his chariot wheels and a gaily-clad youth, with eager enthusiasm in his upturned gaze, lifts aloft a banner bearing Cæsar’s well-known motto, Veni, vidi, vici, to meet the victor’s eyes.

This subject now forms the last of the series but Mantegna’s original scheme included a tenth picture which he afterwards abandoned, probably because the hall for which the “Triumphs” were intended was not large enough to contain more than nine.

An engraving, however, remains in which a body of Roman citizens, followed by the first ranks of the advancing legions, are represented marching in the conqueror’s progress; and the great procession, after reaching its culminating point, is thus brought to a tranquil close. Goethe, who knew the “Triumphs,” not indeed in the original, but from Andreani’s engravings, and who wrote a masterly criticism on the series, was the first to feel the need of a final scene to satisfy the eye, and to point out that this must have been the artist’s original design.

Such, then, are the principal parts of this magnificent work, in which the love of antiquity, which was the ruling power of Mantegna’s genius, found its highest expression. It was a sentiment common to many artists in this age of revived learning, but while other men, like Botticelli or Piero della Francesca, saw pagan themes through the colouring of their own medieval fancies, he alone entered thoroughly into the true spirit of ancient art.

A glance at the “Triumphs” is sufficient to show us how profoundly Mantegna had studied classical authors and how much freedom he had acquired in dealing with his subject.

Part of the Triumphs of Julius Cæsar. By Mantegna.

At Hampton Court.

Those ancient Romans are no strangers to him; he has lived among them and mingled with them as freely as with men of his own day, the folds of their draperies, their very [41]gait and countenance are all familiar to him. The same intimate knowledge of Roman times reveals itself in a hundred details; in the temples and viaducts of the background, in the mythological reliefs which adorn chariots, shields and breast-plates, in tablets bearing Latin inscriptions, in the triumphal arch under which Cæsar passes as he goes on his way. And here we may notice that Andrea, in one of the reliefs of this arch, has again introduced the “Twins” of Monte Cavallo, which during his visit to Rome he had doubtless seen with his own eyes in their time-honoured place on the Quirinal hill.

In the execution of the “Triumphs” we observe the same high degree of finish, as in all his later work; the drapery hangs in the small folds of Greek sculpture, but without stiffness or formality; while the light and transparent colouring is admirably adapted in its softly-shaded tints to the general character of the subject. Evidently in this it was Mantegna’s intention to imitate as closely as possible the style of ancient painting. Unfortunately most of the pictures have suffered from repainting, and at the present day it needs a very minute examination to appreciate the delicacy of the fragments that have been left untouched.

Both in the plastic tendency of form and in the principles of perspective which Mantegna has here successfully applied, we see the result of his earlier studies, modified and restrained by the experience of the thirty years which had passed since the days when he painted the Eremitani frescoes. Nothing can surpass the manner in which the whole of the splendid pageantry of the “Triumphs” is subdued and governed by the laws of composition, till every figure moves in perfect rhythm and harmony of line. We have only to look at the episode of the “Triumphs” by Rubens (in the National Gallery) to see how the subject, released from the severe restraint of Mantegna’s art, could degenerate into a Bacchanalian [42]feast of wild beasts, revellers, and dancing women. But for all its sculptured tendencies and likenesses to a classic frieze, this great series is no procession of marble statues, cold and rigid in their antique beauty. The forms which pass before us in the long array are animated with life and warmth, their faces glow with the fire of human passion in all its endless varieties. Tender and youthful, or worn by age and care, exultant with the joy of victory, or bowed down to earth by a cruel fate, they are men and women like ourselves, and appeal to us by the instincts of a common humanity. In the well-known words of Goethe, “The study of the antique supplies form, nature gives movement and the last touch of life.”

For more than a century the “Triumphs” of Mantegna remained in the hall of the palace for which they had been intended, and were seen there both by Vasari and the historian Mario Equicola. On festive occasions they were sometimes moved to the Castello di Corte, and in Andrea’s lifetime they were used as stage decorations when the comedies of Plautus and Terence were performed at the Court of Mantua.

Several separate episodes of the “Triumphs” were engraved by Mantegna himself, and the complete series became generally known by the publication of the large wood-cuts by Andrea Andreani at the close of the sixteenth century.

In 1628, a short time before the sack of Mantua, the pictures themselves were sold to Charles I., with several other masterpieces of the Gonzaga collection. After that monarch’s death on the scaffold they were again sold by the Parliament, but Cromwell bought them for £1,000.[3] Charles II. placed them in the palace at Hampton Court. There this precious series still remains, irreparably injured by frequent removal and repainting, but [43]still in beauty and completeness both of design and execution one of the most remarkable works of the Italian Renaissance.